Heralded as “The Under-Water Serengeti of Planet Earth,” Palau boasts an astonishing diversity and abundance of healthy corals. Over 700 species of corals have been described from Palau’s reefs within an uncountable number of habitat types. From physically protected salt water lakes to current swept wonderlands, Palau’s limestone islands have created a natural oasis for coral growth.

The coral animal is essentially and upside down jellyfish trapped with a Calcium Carbonate stony skeleton. With waving nocturnal tentacles, the coral animal (polyp) captures microscopic food items (zooplankton) with sting cells (cnidoblasts) and carries the stunned prey to their mouth. Corals can also indirectly receive energy from the sun as they have single celled algae within their tissues (zooxanthellae). The Zooxanthellae photosynthesize to produce sugars which are then commandeered by the coral to fuel their insatiable growth. Thus many species of corals grow much like plants, competing for precious light among the sunbathed reefs.

The coral polyps grow by asexual budding, whereby they literally split in two, eventually forming colonies of effective clones. Depending on the species and habitat, this process of budding can take place within days, months, or even years. Corals can also reproduce sexually by releasing masses of sperm and eggs. This magnificent spawning spectacle can be seen in Palau every April just after the first full moon of the month. Paddling Palau founder Ron Leidich worked for three years along with the researchers from the Palau International Coral Reef Center in an effort to study and understand this coral spawning phenomena.

With over 300 limestone islands, 70+ salt water lakes, 3000’ vertical drop-offs, and hundreds of shallow water patch reefs, it’s no wonder Palau’s coral community is so diverse. The corals growing within the shelter of the vertical limestone islands must by nature be tolerant of the shade. They tend to grow more slowly than their sun loving counterparts, but are interestingly far more colorful. Without winds or waves to disturb their growth, many of the rock island coral gardens are thousands of years old and are thus appropriately known as Old Growth Coral Forests. Within these physical sanctuaries, the corals continue growing until only the neighbors waving stinging cells on long sweeper tentacles ward them off. Within this mosaic of ancient growth one can easily discern Hostile Take-Overs between warring corals and even DMZ’s between even matched foes.

This old growth concept is taken to extreme within the most sheltered bays and lagoons where even typhoon strength winds cannot create so much as a ripple on the calm water. As a result of this total cessation of physical trauma, the corals will often curl up into giant swirling baskets of delicate colonies. The skeletons are so thin that light can shine through their fragile skeletons. The utmost care must be taken when visiting this majestic arena of ancient life.

The coral animal is essentially and upside down jellyfish trapped with a Calcium Carbonate stony skeleton. With waving nocturnal tentacles, the coral animal (polyp) captures microscopic food items (zooplankton) with sting cells (cnidoblasts) and carries the stunned prey to their mouth. Corals can also indirectly receive energy from the sun as they have single celled algae within their tissues (zooxanthellae). The Zooxanthellae photosynthesize to produce sugars which are then commandeered by the coral to fuel their insatiable growth. Thus many species of corals grow much like plants, competing for precious light among the sunbathed reefs.

The coral polyps grow by asexual budding, whereby they literally split in two, eventually forming colonies of effective clones. Depending on the species and habitat, this process of budding can take place within days, months, or even years. Corals can also reproduce sexually by releasing masses of sperm and eggs. This magnificent spawning spectacle can be seen in Palau every April just after the first full moon of the month. Paddling Palau founder Ron Leidich worked for three years along with the researchers from the Palau International Coral Reef Center in an effort to study and understand this coral spawning phenomena.

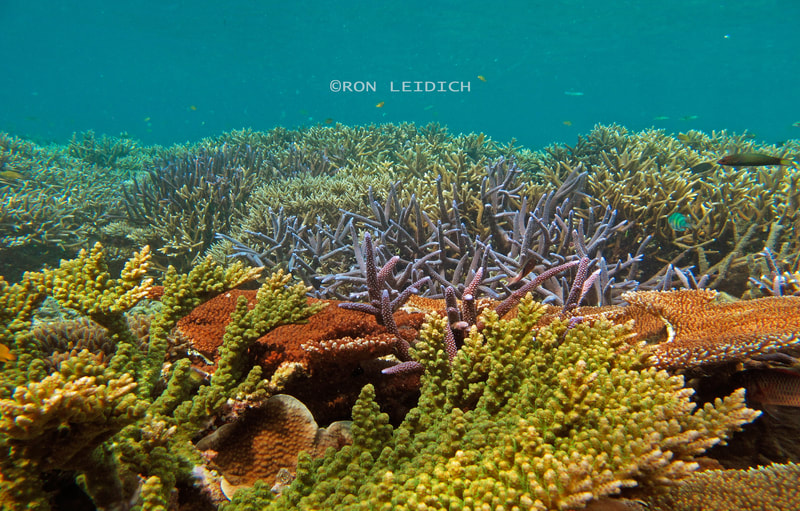

With over 300 limestone islands, 70+ salt water lakes, 3000’ vertical drop-offs, and hundreds of shallow water patch reefs, it’s no wonder Palau’s coral community is so diverse. The corals growing within the shelter of the vertical limestone islands must by nature be tolerant of the shade. They tend to grow more slowly than their sun loving counterparts, but are interestingly far more colorful. Without winds or waves to disturb their growth, many of the rock island coral gardens are thousands of years old and are thus appropriately known as Old Growth Coral Forests. Within these physical sanctuaries, the corals continue growing until only the neighbors waving stinging cells on long sweeper tentacles ward them off. Within this mosaic of ancient growth one can easily discern Hostile Take-Overs between warring corals and even DMZ’s between even matched foes.

This old growth concept is taken to extreme within the most sheltered bays and lagoons where even typhoon strength winds cannot create so much as a ripple on the calm water. As a result of this total cessation of physical trauma, the corals will often curl up into giant swirling baskets of delicate colonies. The skeletons are so thin that light can shine through their fragile skeletons. The utmost care must be taken when visiting this majestic arena of ancient life.

Palau’s patch reefs tend to be bathed in sunlight and are fed by rushing tidal currents. The corals here grow at a much faster rate than their old growth, shaded counter parts. Relying far more heavily on algae-produced sugars, these stunning branching and table top colonies can literally grow like under water weeds. This stunning rate of regeneration helps a reef quickly return after devastation from typhoons, predatory Crown of Thorns Starfish Blooms, and intense thermal stress as was experienced in Palau in 1998. The outer reef corals are periodically subjected to violent storms and enormous waves. Wave exposed reefs are thus by nature less elaborate in growth forms and tend to be stunted by comparison to their inner lagoon counterparts. Despite this ever present physical danger, German Channel leading to the famous Ngemelis drop-off has some of the largest boulder and table corals reaching simply absurd sizes and ridiculous ages. Studies are currently under way to estimate the age of some of these ancient colonies. Some of the larger colonies are likely more than a thousand years old!