|

On Sunday October 22, the Paddling Palau team joined Botanist Benjamin Crain for a day of orchid hunting among the limestone islands. Benny is a visiting scientist from the Smithsonian Institute and is helping to refine Palau's understanding of it's astonishing orchid diversity. Palau boasts at least 80 species of orchids, 28 of which are found nowhere else on earth (endemic species). Dr. Crain hopes to add a few species to our list by closely examining Palau's botanical collection as well as searching for cryptic species in the field. Storm winds from the SW prevented our team from venturing any further out than Ngeruktabel Island. We tucked the boat into "Botany Bay," which is a secluded cove with overhanging Ficus trees dripping with ferns and epiphytes. It proved to be the perfect site to search for orchids. One of the first discoveries was a grove of Shooting Star Orchids, Diplocaulobium elongaticolle in mass bloom. The Ficus tree they were clinging to had spontaneously shed its leaves exposing the orchids to direct sunlight. The added heat stress may explain why so many orchids produced flowers simultaneously. Shortly thereafter Benny spotted Bulbophyllum clandestinum which had previously escaped the view of the Paddling Palau team. With a microscopic flower and miniature leaves it was not surprising that such a "clandestine" species remained unknown to the group of kayak guides. The gem of the day however proved to be the discovery of Oberonia palawensis. As the name suggests, this is one of Palau's 28 endemic species. Though well known to science, this thrilling orchid had never been seen by the Paddling Palau team. Bathed in soft light, the orchid made an idyllic photo subject as they were bearing both flowers and fruits. The hair like seeds are contained within a pod. When the pod dries and bursts open, the seeds are cast out through Ballistic Dispersal. Benny informed us that the seeds contain no endosperm (the nutrients of the seeds). This allows them to remain light weight and float away on air currents. Upon settling, they must then seek out the company of mutualistic fungus, which subsequently feed the germinating orchid until the plant can photosynthesize on its own (and presumably pay back its debt to the fungus).

Much like the King of Fairies, the Oberonia flowers live in hiding and are difficult to find.... and even tougher to photograph! With over 700 native plants, Palau is full of hidden treasures just waiting to be discovered.

1 Comment

September is a special time of year in Palau. The Siberian breeding season has come to an end for a host of migratory species of wading birds, terns, and herons. To escape the onset of winter and ravenous continental predators, flocks of birds take to the wing and fly South on their annual migration. Many of these birds find their way to Palau with precision accuracy to spend the winter in our Micronesian tropical paradise. Other species use Palau as a fueling station where they fatten up on insects, crabs, frogs, and other delectable items before continuing South to Australia or New Zealand. These transitory species are known as Passage Migrants. For some species like the Bar Tailed Godwit this may represent a one way flight distance of over 11,500km. Like any weary traveler, Palau's migratory species show up exhausted and near starving. Our sand flats, mud flats, fresh water ponds, and grasslands provide critical habitat for these fascinating, annual, feathered arrivals.

One of these species in particular makes for an exceptional case study. The Swinhoe's Snipe breeds in Northern Siberia in June & July flying as far South as Northern Australia in the winter. Yes, there truly is a species known as a Snipe. In fact there are at least 25 described species of these wading birds found within three genera. The Snipes are all characterized by a long bill with which they probe into the mud for a variety of invertebrates. Impressively, their bill is equipped with highly specialized filaments leading to sensitive nerve cells. Thus even when the bill is submerged in mud or water and completely out of sight, the Snipes can detect their prey by feel! They even have the ability to feed with their bill closed using a slurping action to deliver prey through their straw like bill. Photographing a snipe can be a monumental task. They are highly cryptic, excessively shy, and difficult to approach. They tend to hide in tall grasses and marsh lands and will disappear into the bush when they feel threatened. When pushed to flight, they take off with monumental speed all the while making numerous cuts and dives. Nineteenth century hunters found them so difficult to shoot on the wing, that any marksman who could knock a Snipe out of the sky became known as a sniper. No kidding, that's the origin of the word Sniper! Palau's commitment to protecting wetland habitat gives the snipes and their migratory relatives a fighting chance at survival in the midst of an ever changing global environment. Take the time to get to know some of our visitors and their fascinating life stories. The migratory birds add another chapter to Palau's global appeal as a wildlife sanctuary and pristine natural habitat. If you've spent any time hiking over limestone "Karst" topography you'll understand what a brutal environment these calcium carbonate rocks create. Razor sharp walls, tumbling boulders, and unstable cliffs are a hiker's nightmare when not following well established trails. Originally formed as ancient coral reefs, uplifted archipelagos like Palau have been exposed to rain water and pounding waves for millennia. The results of 35 million years of erosion in Palau's case has been an exquisite collection of over 300 islands, 70 salt water marine lakes, caves, arches, siphon tunnels, and stunning tropical beaches.

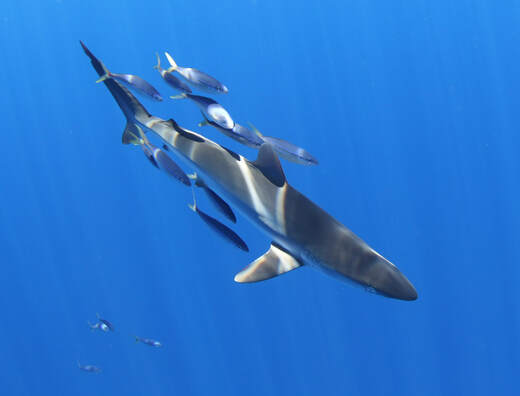

From the air or by boat the islands appear to be lush and green. A closer look at the Botanical assemblage reveals a classic struggle to survive on a rocky, waterless, and nutrient poor environment. Given Palau's staggering marine biodiversity, most visitors arrive in Palau with dreams of multi-colored fish, giant mantas, teaming sharks, and pristine coral gardens. Few adventurers take the time to access the interior of the limestone forests. That's a tragic shame as the Botanical treasures of the Micronesian forests reveal some awe inspiring gems. Not only are the trees and flowers stunningly beautiful but they additionally highlight some magnificent adaptations to "Life on the Limestone." On Saturday September 23rd I paddled into the labyrinth of Palau's rock islands with my two children and some special friends. Our destination was The Valley of the Crotons. I named the site after the beautiful shrubs which are non-native to the limestone environments. Thus this valley was once inhabited or utilized by the people of the rock islands, "Chad era Chelbacheb," who abandoned their villages mysteriously over 500 years ago. This exceptional stretch of forest hides some of Palau's most precious species of trees, shrubs, and orchids. After a short jaunt into the forest we stopped to admire and photograph the colossal buttresses of the native Breadfruit Tree, Artocarpus mariannensis. The seeds can be boiled and eaten while the massive trunks have been used to make the hulls ocean going canoes. The admirable buttresses at first glance would appear to be an adaptation which increases the structural integrity of the trees within a rocky habitat. The solid limestone prevents tap roots from penetrating into the substrate, so this explanation sounds quite logical. However, more recent research suggest that the primary function of the buttress is to increase the surface area for gas exchange. Regardless of function, sitting beneath these magical life forms is a transformative experience. We continued our journey deeper into the canopy covered forest when my daughter spotted an irresistible natural jungle gym. She scampered over boulders and through thick vines to reach the towering prop roots of a strangling fig tree, Ficus microcarpa. The strangling fig begins its life, not on the forest floor like most hard working seeds, but at the top of the canopy, thanks to its delectable fruit. Native pigeons and doves consume the fruit then subsequently deposit the seeds (with fertilizer) on a host tree. The sprouting Ficus then spreads its branches above its host, while dropping its tendril like roots around the host's trunk. The unfortunate victim of the strangler eventually succumbs to starvation after the Fig leaves and branches blanket the host's canopy. Eventually the host tree will decompose leaving a perfect "cast" within the spiral of entangled Fig roots. This natural Botanical chimney provides a most excellent play ground for adventurous 8 year olds with an affinity for heights! Our final destination on the trail of the Botanically incredible, led us to a grove of bizarre trees known as Elaeocarpus rubidus. Sprouting from the base of the trees is a Rastafarian-like tangle of "Dread Lock" roots, which carpet the limestone rocks below. Like a soft woven matt, the sprawling roots make an ideal site for an afternoon nap beneath the cool shade of the forest. When not entertaining human visitors, the Broom Roots as they are often referred once again function to assist in gas exchange. As an air breathing mammal we can relate well to a tree's need to "breath" through its roots. Like us, each tree needs to find a niche, secure a source of water and nutrients, and grow. Ultimately, they flower, produce seeds, and disperse their propagules far and wide to continue the circle of life. As my own little offspring meandered back down the track to our waiting kayaks, I stopped to consider how much we have in common with the quiet giants we humbly walk amongst. |

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed